This is a post about journalism, privacy, and the common assumption that we can’t have one without sacrificing at least some of the other, because (the assumption goes), the business model for journalism is tracking-based advertising, aka adtech.

I’ve been fighting that assumption for a long time. People vs. Adtech is a collection of 129 pieces I’ve written about it since 2008. At the top of that collection, I explain,

I have two purposes here:

-

To replace tracking-based advertising (aka adtech) with advertising that sponsors journalism, doesn’t frack our heads for the oil of personal data, and respects personal freedom and agency.

-

To encourage journalists to grab the third rail of their own publications’ participation in adtech.

I bring that up because Farhad Manjoo (@fmanjoo) of The New York Times grabbed that third rail, in a piece titled I Visited 47 Sites. Hundreds of Trackers Followed Me.. He grabbed it right here:

News sites were the worst

Among all the sites I visited, news sites, including The New York Times and The Washington Post, had the most tracking resources. This is partly because the sites serve more ads, which load more resources and additional trackers. But news sites often engage in more tracking than other industries, according to a study from Princeton.

Bravo.

That piece is one in a series called the Privacy Project, which picks up where the What They Know series in The Wall Street Journal left off in 2013. (The Journal for years had a nice shortlink to that series: wsj.com/wtk. It’s gone now, but I hope they bring it back. Julia Angwin, who led the project, has her own list.)

Knowing how much I’ve been looking forward to that rail-grab, people have been pointing me both to Farhad’s piece and a critique of it by Ben Thompson in Stratechery, titled Privacy Fundamentalism. On Farhad’s side is the idealist’s outrage at all the tracking that’s going on, and on Ben’s side is the realist’s call for compromise. Or, in his words, trade-offs.

I’m one of those privacy fundamentalists (with a Manifesto, even), so you might say this post is my push-back on Ben’s push-back. But what I’m looking for here is not a volley of opinion. It’s to enlist help, including Ben’s, in the hard work of actually saving journalism, which requires defeating tracking-based adtech, without which we wouldn’t have most of the tracking that outrages Farhad. I explain why in Brands need to fire adtech:

Let’s be clear about all the differences between adtech and real advertising. It’s adtech that spies on people and violates their privacy. It’s adtech that’s full of fraud and a vector for malware. It’s adtech that incentivizes publications to prioritize “content generation” over journalism. It’s adtech that gives fake news a business model, because fake news is easier to produce than the real kind, and adtech will pay anybody a bounty for hauling in eyeballs.

Real advertising doesn’t do any of those things, because it’s not personal. It is aimed at populations selected by the media they choose to watch, listen to or read. To reach those people with real ads, you buy space or time on those media. You sponsor those media because those media also have brand value.

With real advertising, you have brands supporting brands.

Brands can’t sponsor media through adtech because adtech isn’t built for that. On the contrary, >adtech is built to undermine the brand value of all the media it uses, because it cares about eyeballs more than media.

Adtech is magic in this literal sense: it’s all about misdirection. You think you’re getting one thing while you’re really getting another. It’s why brands think they’re placing ads in media, while the systems they hire chase eyeballs. Since adtech systems are automated and biased toward finding the cheapest ways to hit sought-after eyeballs with ads, some ads show up on unsavory sites. And, let’s face it, even good eyeballs go to bad places.

This is why the media, the UK government, the brands, and even Google are all shocked. They all think adtech is advertising. Which makes sense: it looks like advertising and gets called advertising. But it is profoundly different in almost every other respect. I explain those differences in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff…

To fight adtech, it’s natural to look for help in the form of policy. And we already have some of that, with the GDPR, and soon the CCPA as well. But really we need the tech first. I explain why here:

In the physical world we got privacy tech and norms before we got privacy law. In the networked world we got the law first. That’s why the GDPR has caused so much confusion. It’s the regulatory cart in front of the technology horse. In the absence of privacy tech, we also failed to get the norms that would normally and naturally guide lawmaking.

So let’s get the tech horse back in front of the lawmaking cart. With the tech working, the market for personal data will be one we control. For real.

If we don’t do that first, adtech will stay in control. And we know how that movie goes, because it’s a horror show and we’re living in it now.

The tech horse is a collection of tools that provide each of us with ways both to protect our privacy and to signal to others what’s okay and what’s not okay, and to do both at scale. Browsers, for example, are a good model for that. They give each of us, as users, scale across all the websites of the world. We didn’t have that when the online world for ordinary folk was a choice of Compuserve, AOL, Prodigy and other private networks. And we don’t have it today in a networked world where providing “choices” about being tracked are the separate responsibilities of every different site we visit, each with its own ways of recording our “consents,” none of which are remembered, much less controlled, by any tool we possess. You don’t need to be a privacy fundamentalist to know that’s just fucked.

But that’s all me, and what I’m after. Let’s go to Ben’s case:

…my critique of Manjoo’s article specifically and the ongoing privacy hysteria broadly…

Let’s pause there. Concern about privacy is not hysteria. It’s a simple, legitimate, and personal. As Don Marti and and I (he first) pointed out, way back in 2015, ad blocking didn’t become the biggest boycott in world history in a vacuum. Its rise correlated with the “interactive” advertising business giving the middle finger to Do Not Track, which was never anything more than a polite request not to be followed away from a website:

Retargeting, (aka behavioral retargeting) is the most obvious evidence that you’re being tracked. (The Onion: Woman Stalked Across Eight Websites By Obsessed Shoe Advertisement.)

Likewise, people wearing clothing or locking doors are not “hysterical” about privacy. That people don’t like their naked digital selves being taken advantage of is also not hysterical.

Back to Ben…

…is not simply about definitions or philosophy. It’s about fundamental assumptions. The default state of the Internet is the endless propagation and collection of data: you have to do work to not collect data on one hand, or leave a data trail on the other.

Right. So let’s do the work. We haven’t started yet.

This is the exact opposite of how things work in the physical world: there data collection is an explicit positive action, and anonymity the default.

Good point, but does this excuse awful manners in the online world? Does it take off the table all the ways manners work well in the offline world—ways that ought to inform developments in the online world? I say no.

That is not to say that there shouldn’t be a debate about this data collection, and how it is used. Even that latter question, though, requires an appreciation of just how different the digital world is from the analog one.

Consider it appreciated. (In my own case I’ve been reveling in the wonders of networked life since the 80s. Examples of that are this, this and this.)

…the popular imagination about the danger this data collection poses, though, too often seems derived from the former [Stasi collecting highly personal information about individuals for very icky purposes] instead of the fundamentally different assumptions of the latter [Google and Facebook compiling massive amounts of data to be read by machines, mostly for non- or barely-icky purposes]. This, by extension, leads to privacy demands that exacerbate some of the Internet’s worst problems.

Such as—

• Facebook’s crackdown on API access after Cambridge Analytica has severely hampered research into the effects of social media, the spread of disinformation, etc.

True.

• Privacy legislation like GDPR has strengthened incumbents like Facebook and Google, and made it more difficult for challengers to succeed.

True.

Another bad effect of the GDPR is urging the websites of the world to throw insincere and misleading cookie notices in front of visitors, usually to extract “consent” that isn’t, to exactly what the GDPR was meant to thwart.

• Criminal networks from terrorism to child abuse can flourish on social networks, but while content can be stamped out private companies, particularly domestically, are often limited as to how proactively they can go to law enforcement; this is exacerbated once encryption enters the picture.

True.

Again, this is not to say that privacy isn’t important: it is one of many things that are important. That, though, means that online privacy in particular should not be the end-all be-all but rather one part of a difficult set of trade-offs that need to be made when it comes to dealing with this new reality that is the Internet. Being an absolutist will lead to bad policy (although encryption may be the exception that proves the rule).

It can also lead to good tech, which in turn can prevent bad policy. Or encourage good policy.

Towards Trade-offs

The point of this article is not to argue that companies like Google and Facebook are in the right, and Apple in the wrong — or, for that matter, to argue my self-interest. The truth, as is so often the case, is somewhere in the middle, in the gray.

Wearing pants so nobody can see your crotch is not gray. That an x-ray machine can see your crotch doesn’t make personal privacy gray. Wrong is wrong.

To that end, I believe the privacy debate needs to be reset around these three assumptions:

• Accept that privacy online entails trade-offs; the corollary is that an absolutist approach to privacy is a surefire way to get policy wrong.

No. We need to accept that simple and universally accepted personal and social assumptions about privacy offline (for example, having the ability to signal what’s acceptable and what is not) is a good model for online as well.

I’ll put it another way: people need pants online. This is not an absolutist position, or even a fundamentalist one. The ability to cover one’s private parts, and to signal what’s okay and what’s not okay for respecting personal privacy are simple assumptions people make in the physical world, and should be able to make in the connected one. That it hasn’t been done yet is no reason to say it can’t or shouldn’t be done. So let’s do it.

• Keep in mind that the widespread creation and spread of data is inherent to computers and the Internet,

Likewise, the widespread creation and spread of gossip is inherent to life in the physical world. But that doesn’t mean we can’t have civilized ways of dealing with it.

and that these qualities have positive as well as negative implications; be wary of what good ideas and positive outcomes are extinguished in the pursuit to stomp out the negative ones.

Tracking people everywhere so their eyes can be stabbed with “relevant” and “interest-based” advertising, in oblivity to negative externalities, is not a good idea or a positive outcome (beyond the money that’s made from it). Let’s at least get that straight before we worry about what might be extinguished by full agency for ordinary human beings.

To be clear, I know Ben isn’t talking here about full agency for people. I’m sure he’s fine with that. He’s talking about policy in general and specifically about the GDPR. I agree with what he says about that, and roughly about this too:

• Focus policy on the physical and digital divide. Our behavior online is one thing: we both benefit from the spread of data and should in turn be more wary of those implications. Making what is offline online is quite another.

Still, that doesn’t mean we can’t use what’s offline to inform what’s online. We need to appreciate and harmonize the virtues of both—mindful that the online world is still very new, and that many of the civilized and civilizing graces of life offline are good to have online as well. Privacy among them.

Finally, before getting to the work that energizes us here at ProjectVRM (meaning all the developments we’ve been encouraging for thirteen years), I want to say one final thing about privacy: it’s a moral matter. From Oxford, via Google: “concerned with the principles of right and wrong behavior” and “holding or manifesting high principles for proper conduct.”

Tracking people without their clear invitation or a court order is simply wrong. And the fact that tracking people is normative online today doesn’t make it right.

Shoshana Zuboff’s new book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, does the best job I know of explaining why tracking people online became normative—and why it’s wrong. The book is thick as a brick and twice as large, but fortunately Shoshana offers an abbreviated reason in her three laws, authored more than two decades ago:

First, that everything that can be automated will be automated. Second, that everything that can be informated will be informated. And most important to us now, the third law: In the absence of countervailing restrictions and sanctions, every digital application that can be used for surveillance and control will be used for surveillance and control, irrespective of its originating intention.

I don’t believe government restrictions and sanctions are the only ways to countervail surveillance capitalism (though uncomplicated laws such as this one might help). We need tech that gives people agency and companies better customers and consumers. From our wiki, here’s what’s already going on. And, from our punch list, here are some exciting TBDs, including many already in the works already:

- Journalism: Remake the whole practice of no-bullshit story-telling by making it fully relevant and driven by the very people who are not only interested, but in the best position to know and tell.

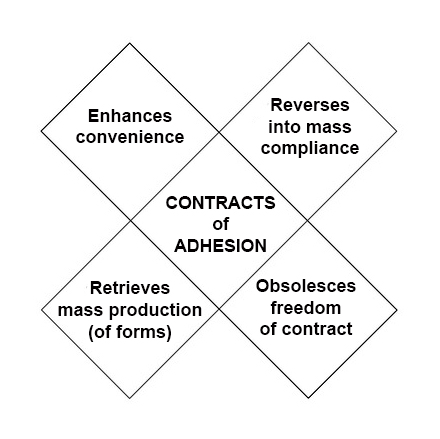

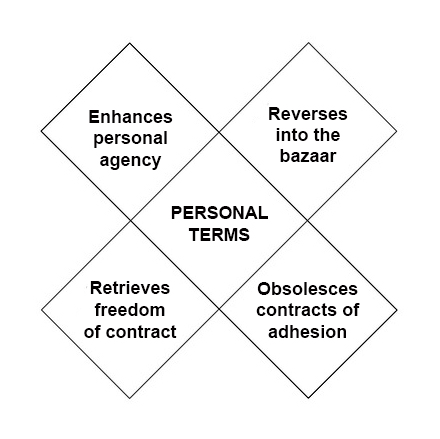

- Terms: Make companies agree to our terms, rather than the other way around. This means making our terms easily readable and mutually beneficial, and with simple ways to resolve disputes.

- Identity: Control our own self-sovereign identities, revealing to businesses no more than what they need to know about us, on an as-needed basis.

- Authentication: Get rid of logins and passwords. (Yes, there is already work going on here.)

- Change of address: We should be able to change our surname or our home address in the records of every organization we deal with, in one move. (Here’s one way.)

- Paying for stuff: Pay what we want, where we want, for whatever we want, in our own ways.

- Zero knowledge commerce: See here.

- Customer service: Call for service or support in one simple and straightforward way of our own, rather than in as many ways as there are 800 numbers to call and punch numbers into a phone before we wait on hold while bad music plays.

- Loyalty: Express loyalty in our own ways, which are genuine rather than coerced. This will make loyalty programs mean what they say.

- IoT: Design and equip the Internet of MY Things, which each of us controls for ourselves, and in which every thing we own has its own cloud, which we control as well.

- Health and fitness: Own and control all our health and fitness records, for the good of all those who need that data, as well as our selves.

- Shared intelligence: Create a standard path for market intelligence that flows both ways, generously and with permission at both ends. This includes how products and services are used.

- Wallets: Have wallets of our own, rather than only those provided by platforms. Here’s one.

- Shopping carts: Have shopping carts of our own, which we can take from store to store and site to site online, rather than being tied to ones provided only by the stores themselves. More here.

- Truly personal mobile devices: Have personal devices of our own (such as this one) that aren’t prisoners in a corporate walled garden, or suction cups on corporate tentacles.

- VRM<—>CRM: Have real relationships with companies, based on open standards and code, rather than relationships trapped inside corporate silos.

- Learning: Remake education around the power we all have to teach ourselves and learn from each other, liberating the inherent genius of every student.

I’m hoping Farhad, Ben, and others in a position to help can get behind those too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.