The University of Chicago Press’ summary of How We Became Our Data says author Colin Koopman—

excavates early moments of our rapidly accelerating data-tracking technologies and their consequences for how we think of and express our selfhood today. Koopman explores the emergence of mass-scale record keeping systems like birth certificates and social security numbers, as well as new data techniques for categorizing personality traits, measuring intelligence, and even racializing subjects. This all culminates in what Koopman calls the “informational person” and the “informational power” we are now subject to. The recent explosion of digital technologies that are turning us into a series of algorithmic data points is shown to have a deeper and more turbulent past than we commonly think.

Got that? Good.

Now go over to the book’s Amazon page, do the “look inside” thing and then go to the chapter titled “Redesign: Data’s Turbulent Pasts and Future Paths” (p. 173) and read forward through the next two pages (which is all it allows). In that chapter, Koopman begins to develop “the argument that information politics is separate from communicative politics.” My point with this is that politics are his frames (or what he calls “embankments”) in both cases.

Now take three minutes for A Smart Home Neighborhood: Residents Find It Enjoyably Convenient Or A Bit Creepy, which ran on NPR one recent morning. It’s about a neighborhood of Amazon “smart homes” in a Seattle suburb. Both the homes and the neighborhood are thick with convenience, absent of privacy, and reliant on surveillance—both by Amazon and by smart homes’ residents. In the segment, a guy with the investment arm of the National Association of Realtors says, “There’s a new narrative when it comes to what a home means.” The reporter enlarges on this: “It means a personalized environment where technology responds to your every need. Maybe it means giving up some privacy. These families are trying out that compromise.” In one case the teenage daughter relies on Amazon as her “butler,” while her mother walks home on the side of the street without Amazon doorbells, which have cameras and microphones, so she can escape near-ubiquitous surveillance in her smart ‘hood.

Lets visit three additional pieces. (And stay with me. There’s a call to action here, and I’m making a case for it.)

First, About face, a blog post of mine that visits the issue of facial recognition by computers. Like the smart home, facial recognition is a technology that is useful both for powerful forces outside of ourselves—and for ourselves. (As, for example, in the Amazon smart home.) To limit the former (surveillance by companies), it typically seems we need to rely on what academics and bureaucrats blandly call policy (meaning public policy: principally lawmaking and regulation).

As this case goes, the only way to halt or slow surveillance of individuals by companies is to rely on governments that are also incentivized (to speed up passport lines, solve crimes, fight terrorism, protect children, etc.) to know as completely as possible what makes each of us unique human beings: our faces, our fingerprints, our voices, the veins in our hands, the irises of our eyes. It’s hard to find a bigger hairball of conflicting interests and surely awful outcomes.

Second, What does the Internet make of us, where I conclude with this:

My wife likens the experience of being “on” the Internet to one of weightlessness. Because the Internet is not a thing, and has no gravity. There’s no “there” there. In adjusting to this, our species has around two decades of experience so far, and only about one decade of doing it on smartphones, most of which we will have replaced two years from now. (Some because the new ones will do 5G, which looks to be yet another way we’ll be captured by phone companies that never liked or understood the Internet in the first place.)

But meanwhile we are not the same. We are digital beings now, and we are being made by digital technology and the Internet. No less human, but a lot more connected to each other—and to things that not only augment and expand our capacities in the world, but replace and undermine them as well, in ways we are only beginning to learn.

Third, Mark Stahlman’s The End of Memes or McLuhan 101, in which he suggests figure/ground and formal cause as bigger and deeper ways to frame what’s going on here. As Mark sees it (via those two frames), the Big Issues we tend to focus on—data, surveillance, politics, memes, stories—are figures on a ground that formally causes all of their forms. (The form in formal cause is the verb to form.) And that ground is digital technology itself. Without digital tech, we would have little or none of the issues so vexing us today.

The powers of digital tech are like those of speech, tool-making, writing, printing, rail transport, mass production, electricity, railroads, automobiles, radio and television. As Marshall McLuhan put it (in The Medium is the Massage), each of new technology is a cause that “works us over completely” while it’s busy forming and re-forming us and our world.

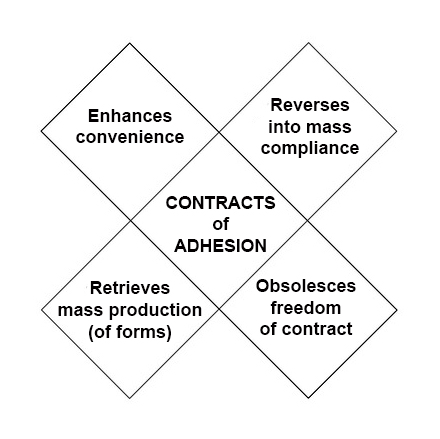

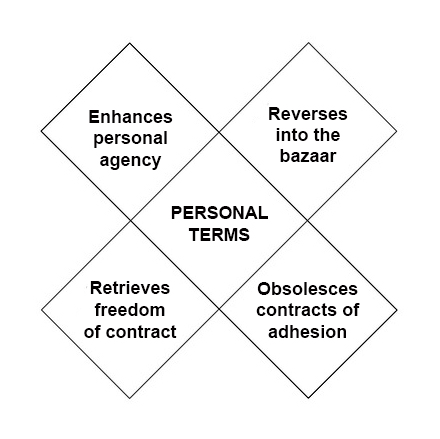

McLuhan also teaches that each new technology retrieves what remains useful about the technologies it obsolesces. Thus writing retrieved speech, printing retrieved writing, radio retrieved both, and TV retrieved radio. Each new form was again a formal cause of the good and bad stuff that worked over people and their changed worlds. (In modern tech parlance, we’d call the actions of formal cause “disruptive.”)

Digital tech, however, is less disruptive and world-changing than it is world-making. In other words, it is about as massively formal (as in formative) as tech can get. And it’s as hard to make sense of this virtual world than it is to sense roundness in the flat horizons of our physical one. It’s also too easy to fall for the misdirections inherent in all effects of formal causes. For example, it’s much easier to talk about Trump than about what made him possible. Think about it: absent of digital tech, would we have had Trump? Or even Obama? McLuhan’s blunt perspective may help. “People,” he said, “do not want to know why radio caused Hitler and Gandhi alike.”

So here’s where I am now on all this:

- We have not become data. We have become digital, while remaining no less physical. And we can’t understand what that means if we focus only on data. Data is more effect than cause.

- Politics in digital conditions is almost pure effect, and those effects misdirect our attention away from digital as a formal cause. To be fair, it is as hard for us to get distance on digital as it is for a fish to get distance on water. (David Foster Wallace to the Kenyon College graduating class of 2005: Greetings parents and congratulations to Kenyon’s graduating class of 2005. There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”)

- Looking to policy for cures to digital ills is both unavoidable and sure to produce unintended consequences. For an example of both, look no farther than the GDPR. In effect (so far), it has demoted human beings to mere “data subjects,” located nearly all agency with “data controllers” and “data processors,” has done little to thwart unwelcome surveillance, and has caused boundlessly numerous, insincere and misleading “cookie notices”—almost all of which are designed to obtain “consent” to what the regulation was meant to stop. In the process it has also called into being monstrous new legal and technical enterprises, both satisfying business market demand for ways to obey the letter of the GDPR while violating its spirit. (Note: there is still hope for applying the the GDPR. But let’s get real: demand in the world of sites and services for violating the GDPR’s spirit, and for persisting in the practice of surveillance capitalism, far exceeds demand for compliance and true privacy-respecting behavior. Again, so far.)

- Power is moving to the edge. That’s us. Yes, there is massive concentration of power and money in the hands of giant companies on which we have become terribly dependent. But there are operative failure modes in all those companies, and digital tech remains ours no less than theirs.

I could make that list a lot longer, but that’s enough for my main purpose here, which is to raise the topic of research.

ProjectVRM was conceived in the first place as a development and research effort. As a Berkman Klein Center project, in fact, it has something of an obligation to either do research, or to participate in it.

We’ve encouraged development for thirteen years. Now some of that work is drifting over to the Me2B Alliance which has good leadership, funding and participation. There is also good energy in the IEEE 7012 working group and Customer Commons, both of which owe much to ProjectVRM.

So perhaps now is a good time to start at least start talking about research. Two possible topics: facial recognition and smart homes. Anyone game?

What turns out to be a draft version of this post ran on the ProjectVRM list. If you’d like to help, please subscribe and join in on that link. Thanks.

From the

From the

The

The difference between Phase One and Phase Two is

difference between Phase One and Phase Two is  Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed

Next steps in tracking protection and ad blocking. At the last VRM Day and IIW, we discussed  Small businesses and their customers both have problems dealing with big businesses that are more vested in captive markets than in free ones. So, since VRM is about independence and engagement, we may have an opportunity for customers and small businesses to join in common cause.

Small businesses and their customers both have problems dealing with big businesses that are more vested in captive markets than in free ones. So, since VRM is about independence and engagement, we may have an opportunity for customers and small businesses to join in common cause.

You must be logged in to post a comment.